In late 2007, President Olusegun Obasanjo sold majority stakes in two Nigerian refineries to a private consortium called Bluestar led by Nigerian tycoon Aliko Dangote for $761 million. The move sparked an intense backlash – trade unions claimed the sales price severely undervalued the refineries.

They also labeled the deal a crony one because investors in the consortium, Aliko Dangote and Femi Otedola among others were Obasanjo’s allies.

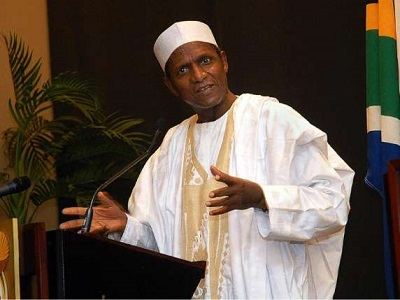

Upon assuming office, President Umaru Yar’adua swiftly reversed the sales, returning the refineries to the state-owned Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC). Although, he aimed to quell public anger, but the question lingers – did this decision plunge Nigeria into an economic crisis that still haunts us today?

At first, Yar’adua’s actions earned praise, reducing petrol prices from ₦75 to ₦65 per liter in 2007. He awarded NNPC $52 million to repair the Chanomi pipeline feeding Warri and Kaduna refineries after militant attacks.

However, fast forward to 2024, Nigeria’s four refineries lie in perpetual disrepair despite over $19 billion spent under President Buhari’s administration, according to ex-MD of African Petroleum now Governor of Nasarawa, Abdullahi Sule. The current government has had to finally end fuel subsidies after years of hemorrhaging state resources.

Meanwhile, ex-President Obasanjo insists the refineries can never work under state control and should have been privatized. So, did Yar’adua’s politically motivated reversal sow the seeds of Nigeria’s downstream crisis?

The arguments around privatization remain heated and complex even now. With the Nigerian government strapped for funds, private investment is undoubtedly needed to rehabilitate dilapidated refineries. However, sale terms must also ensure national interests are secured, not just profits for new owners.

Yar’adua felt the Obasanjo-era sales failed this test, designed to benefit allies, not Nigeria. But reversing course also meant assets that could have been operational and yielding returns for years remained moribund.

In the end, while his intentions to protect state assets were reasonable, Yar’adua’s reversals set Nigeria back. With no immediate private capital or expertise injected, refineries kept deteriorating as NNPC mismanaged turnaround projects.

Perhaps if sales had gone through on fair terms back in 2007, private owners would have revamped and ran refineries profitably years ago without endless government funding. While the social impacts of deregulation require care, Nigeria may have shot itself in the foot by reversing course.

Since, No administration has shown the ability to resuscitate these strategic assets, except for President Tinubu who oversaw rehabilitation of the Port Harcourt Refining Company Limited (PHRC) which recently received supply of over 475,000 barrels of crude oil.

In the end, Yar’adua may have acted to remedy what he saw as an unfair deal, but the long-term impacts have been disastrous and plunged Nigeria into downstream chaos.